This topic takes on average 55 minutes to read.

There are a number of interactive features in this resource:

Chemistry

Chemistry

Influenza – better known as 'flu – is a killer. Every year several thousand people in the UK alone die of 'flu or diseases such as pneumonia, which can follow a 'flu infection. Globally the WHO estimates that between 250,000 and 500,000 people die each year from this disease of the breathing system.

Influenza is caused by a virus. Influenza viruses have many different antigens on their surfaces. The viruses often mutate causing the antigens to change from year to year. Two important antigens on the influenza virus are the H antigen which is linked to the way the virus gets into the host cell and the N antigen which helps release the new viruses from an infected cell. These major antigens can change dramatically. When they do, an entirely new strain of influenza emerges.

Each year an influenza vaccine is developed and given to the people who are most at risk of suffering serious complications if they get the influenza. This is mainly older people and people of all ages who work in the health services or are already ill. This vaccine contains the most common influenza viruses in circulation at the time – the ones doctors and scientists consider most likely to cause the next annual influenza outbreak.

Influenza doesn’t just affect people. There are strains of the virus which cause disease in other animals such as birds and pigs. Sometimes the virus which causes bird influenza or swine (pig) influenza mutates and becomes capable of infecting people. These new strains can be particularly serious, because few people have any natural immunity to them.

In March 2009 a new disease appeared in the town of La Gloria in Mexico. 60% of the population became ill and 2 babies died. The government thought this was caused by a form of the H2N3 influenza virus. However at least one infected person tested positive for H1N1 – a form of influenza usually found in pigs.

By the end of March swine influenza appeared in America. By early April, using PCR and the most up-to-date DNA analysis techniques, the virus was again identified as H1N1. Several people died as a result of the infection, they were mainly children and relatively young adults.

By the end of April, the World Health Organisation issued a warning that the new H1N1 swine influenza virus, which had not been seen before in either pigs or people, was threatening to cause a pandemic of disease. Diagnostic tests based on PCR meant that people infected with the virus could be identified fast (see Infection detection and Real time PCR). People in countries as far apart as Scotland, Spain and Canada became infected. By the beginning of June H1N1 was causing disease in 62 countries, and a number of people were dead as a result. The available influenza vaccines were no use against this virus.

By the end of August almost 3000 people around the world had died as a result of H1N1. Although the number of cases was dropping, scientists were racing to produce a vaccine against H1N1 before the traditional influenza season in the winter. The normal influenza vaccine would not offer protection because it did not contain the H1N1 virus.

In September – just 6 months after swine influenza H1N1 was first identified, a vaccine became available and China was the first country to use it, followed by Australia. On 21st October 2009 the UK began its vaccination programme, just in time to help prevent H1N1 taking hold again in the seasonal winter influenza outbreak.

The richer nations made swine influenza vaccines available to poorer countries to help prevent the spread of the disease. But even in countries such as the US and the UK, there wasn’t enough vaccine to go around. In the US alone, nearly 10,000 people died of H1N1 influenza. Eventually influenza vaccine was made available to everyone, not just the very young, the very old and the sick.

By August 2010 the WHO declared the worldwide H1N1 pandemic officially over. PCR had helped contain and minimise the first major influenza pandemic for many years, by helping scientists identify and sequence the virus. This meant that cases could be identified and isolated fast, and that a safe and effective vaccine could be developed very rapidly using existing influenza vaccine technology. In 2010 the H1N1 vaccine became part of the normal seasonal influenza vaccine. In the 2015-16 influenza season, H1N1 viruses were still the most common cause of influenza – but because they had been incorporated in the seasonal influenza vaccines, overall mortality from the disease was relatively low.

The H1N1 pandemic of 2009 has made some scientists question the way we develop influenza vaccines. There are fears that a more virulent strain of influenza could emerge, a mutation of either the swine influenza H1N1 virus or one of the H5N1 viruses which cause bird influenza.

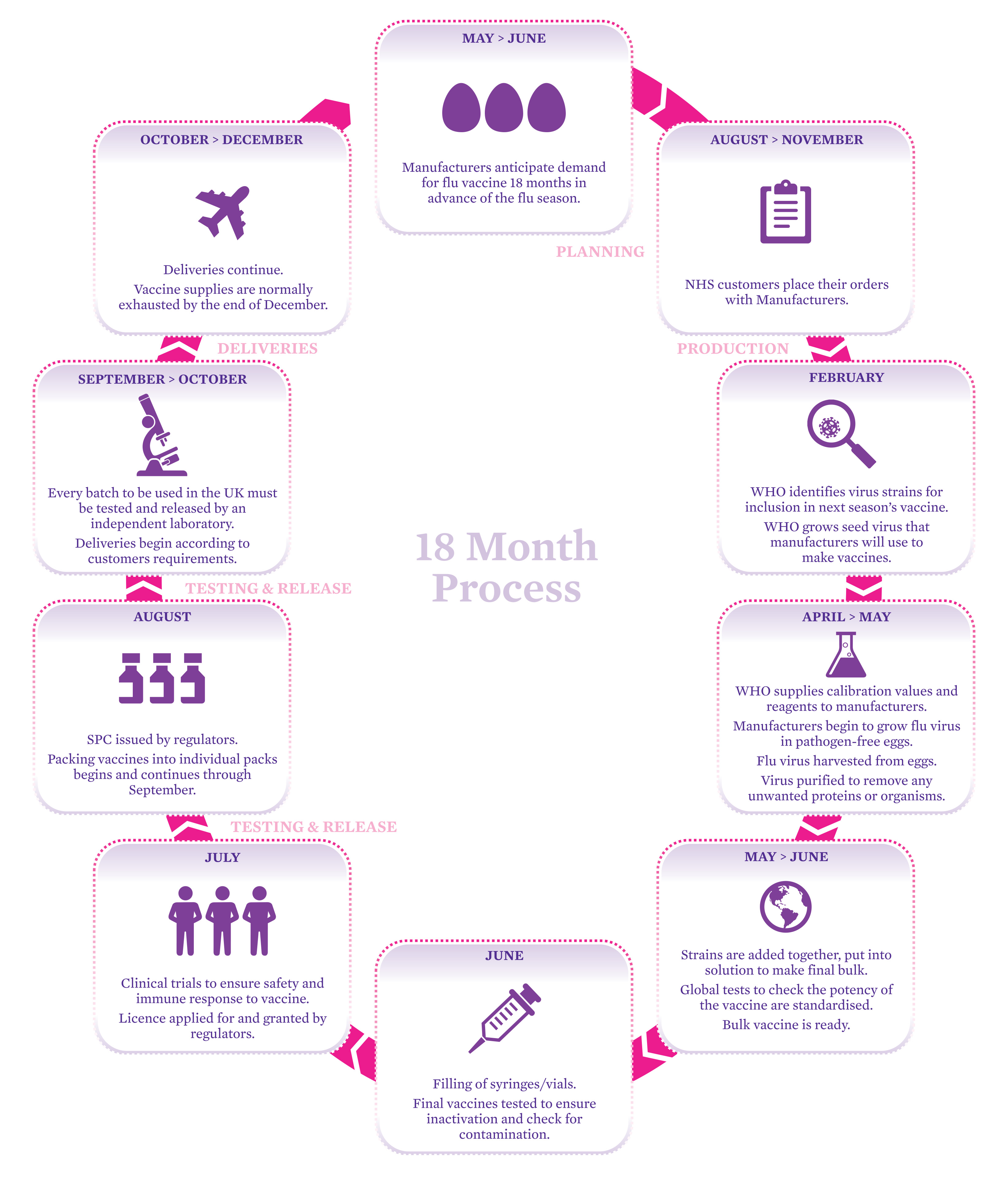

Unfortunately, influenza vaccines are quite complicated and take time to make. After the H1N1 pandemic, and fears of an outbreak of a new form of the H5N1 bird influenza, there is some controversy about what vaccines and how much vaccine should be produced. Research scientists, the vaccine manufacturers and doctors work together each year to try and get the balance right – but sometimes a new strain of the virus emerges undermining all the best-intentioned plans.

See a larger version of the process.

Look in detail at the process of manufacturing the influenza vaccine shown here. Imagine we are in the middle of an influenza epidemic. The media is full of people complaining that the available influenza vaccine is not effective against the new influenza virus. Do some research if you need to and write three blog posts, explaining:

how difficult it is to get the right amount of the right influenza vaccine ready each year

how a new strain of influenza can arise very rapidly

what scientists and manufacturers have to do when a new influenza strain appears to develop and produce a new vaccine in a very short timescale.